Proposal 13 for ICANN: Provide an Adjudication Function by Establishing “Citizen” Juries

28 February 2014

This is the thirteenth of a series of 16 draft proposals developed by the ICANN Strategy Panel on Multistakeholder Innovation in conjunction with the Governance Lab @ NYU for how to design an effective, legitimate and evolving 21st century Internet Corporation for Assigned Names & Numbers (ICANN).

Please share your comments/reactions/questions on this proposal in the comments section of this post or via the line-by-line annotation plug-in.

From Principle to Practice

Legitimate organizations are accountable to their members when they possess “acknowledgement and assumption of responsibility for actions, products, decisions, and policies within the scope of the designated role” they play.[1. Brown, Ian. Research Handbook on Governance of the Internet. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. (2013) at 100.] Accepting responsibility involves both “answerability and enforcement.”[2. Lenard, T.M., White, L.J. “Improving ICANN’s governance and accountability: A policy proposal.” Inf. Econ. Policy (2011). doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2011.03.001 at 5.] There are many routes to adjudication.

Accountability typically is a consequence of both procedural fairness before the fact and adjudicatory processes after the fact to help ensure that decisions serve established goals and broader public interest principles.

As one means to enhance accountability – through greater engagement with the global public during decision-making and through increased oversight of ICANN officials after the fact – ICANN could pilot the use of randomly assigned small public groups of individuals to whom staff and volunteer officials would be required to report over a given time period (i.e. “citizen” juries). The Panel proposes citizen juries rather than a court system, namely because these juries are lightweight, highly democratic and require limited bureaucracy. It is not to the exclusion of other proposals for adjudicatory mechanisms.

What Do We Mean By “Citizen” Juries?

What they are

Citizen juries are randomly assigned small public groups who convene to deliberate on a specific issue, drawing on “witnesses” or stakeholders who present divergent points of view to inform the jury’s deliberation and ultimate recommendation or decision.[3. “Citizen Juries.” Department of Environment and primary Industries. Victoria State Government.]

A main objective of citizen juries is to “draw members of the community into participative processes where the community is distanced from the decision-making process or a process is not seen as being democratic.”[4. Ibid.] Notably, citizen juries are meant to “compliment other forms of consultation rather than replace them.”[5. Ibid.]

How they work

A common model of citizen juries is one that includes about twelve to twenty people or “non-specialists” randomly selected.[8. “Citizen Juries: a radical alternative for social research.” Social Research Update Issue 37. University of Surrey. (Summer 2002).]

The goal of random selection in these small groups is to involve a wider representative sample of a community in decision-making, while empowering participants who have “no formal alignments or allegiances”[9. “Citizen Juries.” Department of Environment and primary Industries. Victoria State Government.] to review specific actions or outcomes. Jury makeup tends to not only to be random, but also “demographically balanced.”[10. Crosby, Ned and Hottinger, John C. “The Citizen Jury Process.” The Council of State Governments: Knowledge Center. July 1, 2011 at 321.]

Citizen jurors meet (traditionally in person) for an extended period of time (typically 2-3 days) to examine a specific issue of “public significance.”[11. “Citizen Juries: a radical alternative for social research.” Social Research Update Issue 37. University of Surrey. (Summer 2002).] Notably, issues submitted to citizen juries tend to be localized. [12. Crosby, Ned and Hottinger, John C. “The Citizen Jury Process.” The Council of State Governments: Knowledge Center. July 1, 2011 at 322.]

During jury meetings, “specialists” often present or discuss various issues related to the given topic being debated/decided and juries are provided with time to reflect and deliberate with each other; interrogate specialists and scrutinize information presented; and develop conclusions or recommendations for action.[13. “Citizen Juries: a radical alternative for social research.” Social Research Update Issue 37. University of Surrey. (Summer 2002).] Citizen juries tend to conclude their deliberations by delivering a report advising future action or directions for the inquiring institution.[14. “Citizen Juries.” Department of Environment and primary Industries. Victoria State Government.]

Notably, establishment of citizen juries has also occurred in some marginalized communities, in a more “bottom-up” fashion.[15. “Citizen Juries: a radical alternative for social research.” Social Research Update Issue 37. University of Surrey. (Summer 2002) (discussing U.K. citizen jury efforts).] Scholars have noted that “citizen juries appear to offer a method of action-research that has a high potential for methodological transparency, participatory deliberation and subsequent citizen advocacy.”[16. Ibid.]

Why Does this Proposal Make Sense at ICANN?

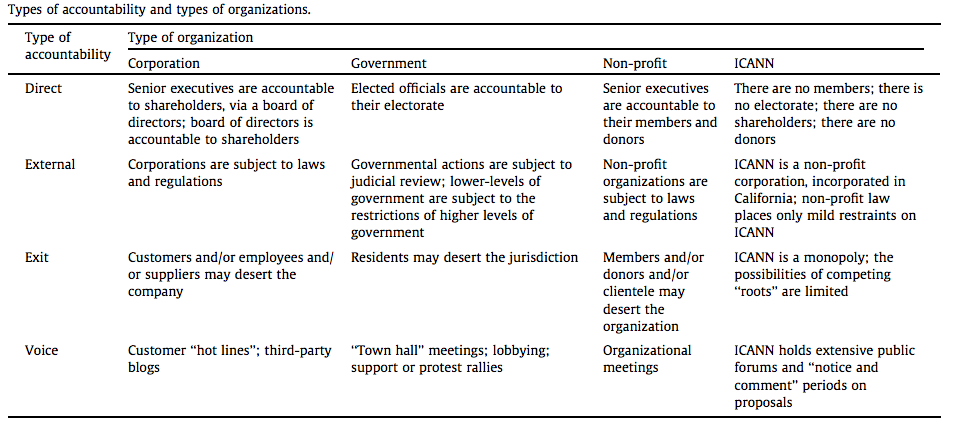

Since its inception, ICANN has committed itself to acting on behalf of the global public, consistent with its core mission and values, as set out in the ICANN Bylaws. However, over the years, scholars and those intimate with ICANN have noted the organization’s shortfalls, asserting that ICANN tends to operate in a manner that is “disconnected from most of the accountability mechanisms that normally accompany a corporation, a standards development organization or a government agency” – all types of entities with which ICANN shares certain similarities. [17. Mueller, Milton. “ICANN, Inc.: Accountability and participation in the governance of critical Internet resources.” Internet Government Partnership. November 16, 2009 at 3.]

Policy (2011), doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2011.03.001.

Furthermore, ICANN tackles issues that affect a wide variety of different stakeholders – from business to government to civil society – differently in different regions around the world. Ensuring sufficient participation and legitimacy of process, not just in the solution-development stage of its work, but also in the evaluation and review stages, requires paying close attention to different localized contexts and fostering feedback loops to ensure outcomes and effects can be analyzed, learned from and evolved in an equitable manner.

As such, establishing “citizen” juries at ICANN has potential to:

- Increase accountability by involving the public in advising on or reviewing Board and leadership actions;

- Create an “audience effect” of having to be open, which improves accountability and also provides an opportunity for outside insights and input;

- “[D]raw members into participative processes where the community is distanced from the decision-making process”[18. “Citizen Juries.” Department of Environment and primary Industries. Victoria State Government.];

- Improve representation by engaging a “cross-section of the community”[19. Ibid.];

- Be useful in “moderat[ing] divergence” on issues and increasing transparency of process[20. Ibid.];

- Provide “jurors” (i.e. community members) an opportunity to build and deepen learnings on specific ICANN issues[21. Ibid.], and to do so collaboratively;

- Monitor or gauge community and public sentiment regarding ICANN’s work and its execution of commitments in the public interest[22. Ibid.];

- Broker conflict or provide “a transparent and non-aligned viewpoint.”[23. Ibid.]

Implementation Within ICANN

Before piloting the establishment and use of citizen juries, ICANN should address and consult its community on the following considerations:

Purpose of Jury – what is the goal or decision you want to ask the jury to make?

- “Citizen” juries have been deployed in relation to a number of different contexts, for example:

- On Issues: “Citizen” juries have most often been formed to consider specific courses of actions in relation to localized issues.[23. Crosby, Ned and Hottinger, John C. “The Citizen Jury Process.” The Council of State Governments: Knowledge Center. July 1, 2011 at 322.]

- To Inform “Voters”: Juries have been used in some contexts to evaluate political candidates and either recommend one for vote or to evaluate candidates on particular issues.[24. Ibid.]

- To Review/Evaluate: Juries have also been used to develop “clear, useful and trustworthy information about ballot measures” in the political context, for example, and have produced key findings and an assessment of particular ballot measures.[25. Ibid.]

- Enabling “citizen” or netizen juries to review actions and policies of the ICANN Board after the fact is one particularly ripe area for implementation, as ICANN currently lacks traditional mechanisms for adjudication after-the-fact that exist, for example, in corporate governance (i.e. ICANN is not expressly accountable to any well-defined “members” or shareholders).

- However, ICANN should consider all options for citizen juries’ capacity within the existing ICANN structure. For instance, enabling cross-community and public deliberation through a citizen jury during the issue-framing or solution development stage of ICANN’s work could help ICANN understand potential outcomes and identify possible impacts of its decisions from new channels, and via processes that embrace deliberation and consensus-building. Perhaps this technique would be best suited for areas of ICANN’s work where no known desired outcomes exist or where outcomes will have divergent impacts on various regions. A citizen-jury could, therefore, help to gauge cross-community and value-based perspectives in a manner that informs the breadth of possible solutions and considerations to be pursued or could provide the ICANN Board with additional input that could help either reinforce traditional problem-solving processes or help to identify areas in which unintended consequences or issues may arise that were not uncovered through formal policy-development processes.

Jury Selection – without members, who’s part of the jury pool?

- While typical citizen juries often comprise a random sampling of individuals, ICANN should consider what constitutes a viable general ICANN public in order to determine what the participant pool looks like.

- Some commenters have advocated for an official membership program within ICANN. However, establishing members by consequence means there are non-members, which poses certain challenges to ICANN’s continued operation as an open, inclusive global organization.

- One means of identifying a candidate pool without formalizing membership could be to using data from those who have participated in ICANN Labs’ Peer Advisory Network, data on ICANN meeting attendance, data shared from other global Internet governance events and organizations, any forthcoming I* expert network data, stakeholder engagement data, data on participation within ICANN structures and possibly data shared by universities and regional or local organizations working in or studying the Internet industry.

- As commenters have noted, much of ICANN’s existing community comprises volunteers, who may be lacking in knowledge on specific issues or time to devote to serving “jury duty.” ICANN should therefore consider whether incentives (including non-monetary ones) could be used to encourage members of the global public to more willingly participate.[26. For examples of different incentives that may be worth testing in this context, see the specific Panel proposal related to games.]

Operation – how do the juries work without having to physically convene, especially across borders?

- Regardless of the specific objective established, ICANN citizen juries should build on the traditional offline model and operate in an open and transparent manner online. Online tools suggested in other Panel proposals would assist in communicating and enabling deliberation across-borders, though undoubtedly, some allocation of “administrative organizational resources from ICANN’s budget” will still be necessary.

- To help maximize value of the citizen jury concept within ICANN, the organization could consider establishing an “ICANN netizen jury handbook” in consultation with the community. Notably, the Jefferson Center’s Citizen Jury Handbook is a great guide to be used in designing any pilot or practice in this field.

- ICANN should also encourage its global community to run localized “juries” that report back to ICANN’s Board or various Councils. This would, of course, require sharing information on Board or Council actions in open, accessible and legible ways with these distributed jury teams.

Presentation to the Jury – how to present evidence relating to complex, specialized issues?

- While citizen juries present an opportunity for fostering an environment where people who know little about ICANN can gain expertise together with others, there is no escaping the fact that ICANN’s work can be complex, technical and specialized.

- Therefore, ICANN staff may prove a vital role in helping establish useful frames for the work of the jury to enable all parties of varying knowledge to be able to converse intelligently on the issues.

- Furthermore, “specialists” or ICANN Board members, stakeholders or community leaders may be paramount in presenting the requisite evidence from competing or divergent perspectives in order to enable citizen juries to meaningfully deliberate on the issue for which they’ve been asked to comment.

- Notably, carrying out this framing and specialist role will also likely support efforts aimed ore generally at finding ways to articulate ICANN’s work in more simplified ways, without losing meaning.

Powers of the Jury – what responsibilities and “rights” should juries have?

- As noted above, typically, the outputs from citizen juries are captured via report or recommended plans for action that can then be evaluated and considered by the soliciting institution. If ICANN adopts this method of jury output, it should consider standardizing how citizen juries report their findings in order to enable future cross-referencing and analysis.

- The ICANN community should also discuss what additional, if any, responsibilities and rights a citizen jury should be afforded (e.g., removal power and/or veto power are those typical in corporate adjudication processes). Establishing what the criteria should be for when exercising those rights and responsibilities would be deemed appropriate by the community is also vital.

- At the very least, ICANN should require that findings from a citizen jury be publicly addressed by the ICANN Board and memorialized along with Board responses in open formats, which are accessible and legible to the public.

Assessing Success – from the perspective of participants

- If ICANN does decide to adopt this proposal, we advocate for testing 2-3 initiatives, making certain to assess the process from the perspective of “jurors”/participants to make sure we can iterate what has worked and what doesn’t over time.

Case Studies – What’s Worked in Practice?

-

The Jefferson Center – Within the United States, the Jefferson Center serves as a leading organization working “to strengthen democracy by improving civic discourse and advancing informed, citizen-led solutions to public policy issues.” It does so by supporting, implementing and studying citizen juries in a variety of contexts – from employment to the economy and U.S. Federal debt to health care. One specific citizen jury initiative undertaken by the Center and Promoting Healthy Democracy focused on 2009 Election Recounts in Minnesota, and was “credited with helping build bipartisan support for reforms to that state’s recount procedures.”[27. “Citizens’ Jury.” Participedia. March 21, 2010.]

-

Citizens’ Initiative Review – Created by Healthy Democracy Oregon & Healthy Democracy Fund, this initiative harnesses the citizen jury model to “publicly evaluat[e] ballot measures so voters have clear, useful, and trustworthy information at election time.” For each measure reviewed a new panel is formed and hears “directly from campaigns for and against the measure and calls upon policy experts during the multi-day public review.”

-

Prajateerpu (“People’s Verdict”) – This initiative took place from 2001-2003 in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (AP), and focused on “future of farming and food security.” Specifically, the initiative aimed to serve as “a means of allowing those people most affected by the government’s ‘Vision 2020’ for food and farming in AP to shape a vision of their own.” A team of marginalized farmers were identified and the processes were conducted in Telegu – the language used by the least affluent.[28. Wakeford, Tom, et al. “The jury is out: How far can participatory projects go towards reclaiming democracy?” Handbook of Action Research. Second Ed. Sage Inc.: New York. (2007) at Chapter 2: 6.] Jurors were “non-literate – reflecting status of majority of state’s citizens – and female, reflecting their greater practical role, but lack of voice, in agriculture.”[29. Ibid.] The state government and U.K. Government’s Department for International Development ultimately changed aid policy within the state as a result of this initiative, which influenced similar processes in Zimbabwe and Mali. Notably, plans to replicate this process within AP were stopped due to a “lack of state/NGO capacity.”[30. Ibid.]

-

Democratizing Agricultural Research – Focusing in South Asia, West Africa, South America and West Asia, this initiative harnesses the citizen jury approach to introduce local voices into the process of developing food and agriculture policy at the local and national levels.

Open Questions – How Can We Bring this Proposal Closer to Implementation?

- What institutional or cultural barriers would pose challenges to implementation?

- How can ICANN select a pool of citizen jurors? What challenges are contained in this selection process?

- How are online and offline models of citizen juries different? For example, what mechanisms might be required for identity verification and authentication, so that the online citizen jury is not “gamed”?

- How can ICANN operationalize a citizens jury process? For example, in which structures or processes might a citizens jury be highly appropriate? If they seem appropriate, how can ICANN institute a citizen jury process in a low-risk context where ICANN can still show proof-of-concept?

- How could ICANN best frame and provide adequate learnings to “jurors” in order to foster meaningful and useful deliberation?

- What powers and rights should be afforded to citizen juries in which contexts?

- Does it make more sense for ICANN to leverage citizen juries before Board deliberations to guide policy-making, after to review decisions, or both?

- Are there specific issues ICANN is dealing with at present where broad public deliberation from the global netizen community would be useful but is lacking?

- What staffing and resource needs would ICANN need to be able to see this proposal to fruition? How would partnering this effort with others (e.g., creation of an open data policy at ICANN) help bolster transparency and accountability within the organization?